Golyong-gol: a hidden history

DIFFICULT HISTORYMODERN HISTORY

A few days ago marked the 75th anniversary of the Daejeon massacre. Between June 28th and July 17th, 1950, thousands of political prisoners, whom authorities feared would join the approaching invading forces from the north, were transported in trucks from Daejeon Prison to their deaths in an area called Golyong-gol. Unlike Daejeon Prison, which still has visible structural remains, Golyong-gol today looks like an idyllic countryside location curving around the base of a mountain. There are no visible traces except for its modern-day usage. But what lies beneath the ground are the remains of eight massacre pits, which in total make up a mass gravesite of around 1km long.

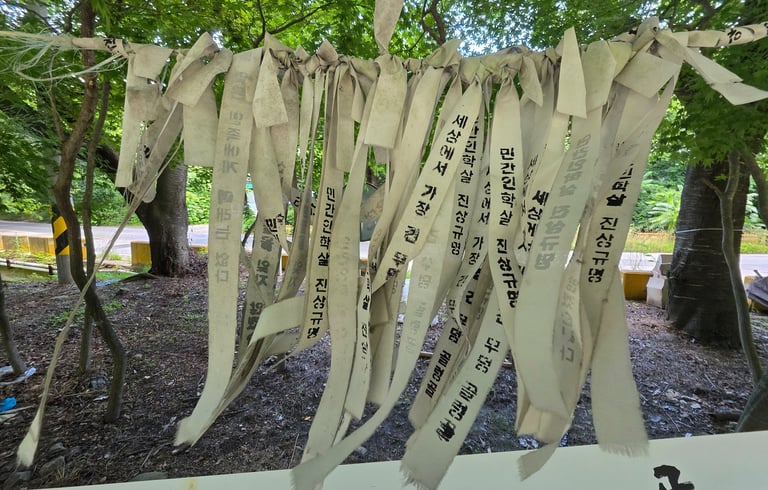

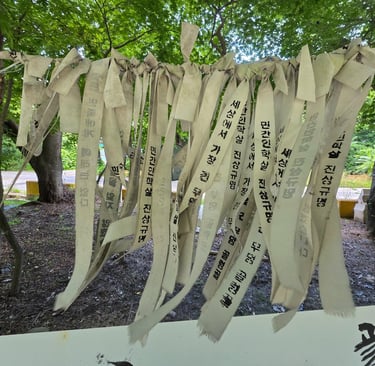

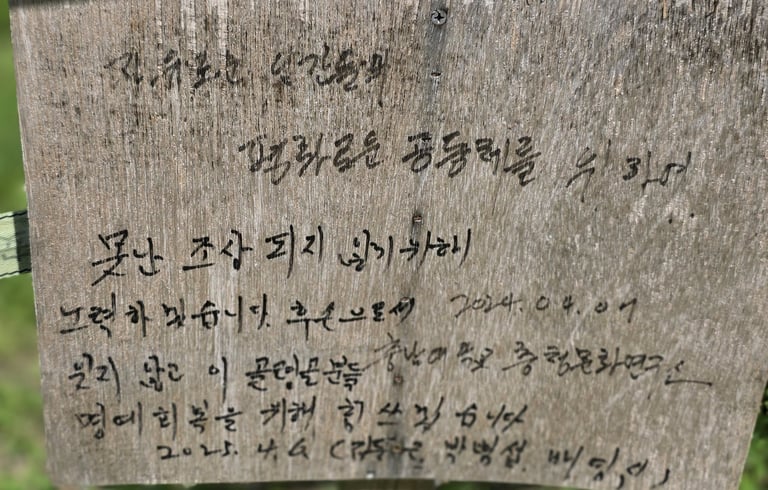

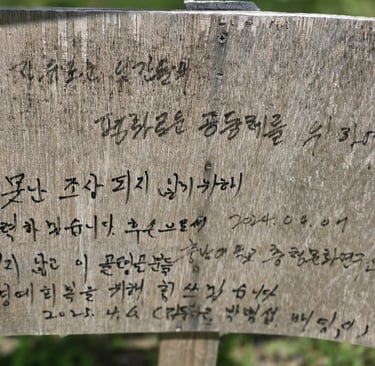

I visited a section of Golyong-gol for the first time on Monday, June 30th, just a few days after the 75th anniversary, and it was clear that people, including descendants, had visited very recently. White ribbons hung on trees and small white plastic windmills were dug into the ground – the colour white being commonly associated with death and funerary rituals, and symbolizing grief, loss and mourning in South Korea. Elsewhere, standing arrangements of fresh white flowers stood in front of two commemorative headstones, weather worn wooden panels with fading messages written in pen were dug into the ground along the edge of the pit and fresh food and alcohol were placed at various locations as offerings to the victims. One of those offerings clearly came from Jeju, indicating that someone had been specifically commemorating victims whom had been incarcerated in Daejeon Prison following the April 3rd uprising.

The events at Golyong-gol occurred due to a clampdown on people throughout the south who were opposed to the division of the country. Many were taken into custody by the police but fears grew that those with leftist political views would join the approaching northern army. This fear resulted in a government order for their execution. Photographic evidence of these events was captured by British journalist Alan Winnington, who published them in a pamphlet entitled I saw the truth in Korea. Today we can see those pictures and part of Winnington’s publication as part of the on-site interpretation. Despite this evidence, these and other similar events went unacknowledged for many years. In 2005, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of the Republic of Korea was established to investigate this and other events related to human rights violations and mass atrocities. The commission was relaunched in 2020 following continued appeals from survivors and their families who were still seeking truth and justice. The work of the commission continues to this day and some of those buried at Golyong-gol have now been recovered, although not all have been identified.

Information boards at the site detail a plan to create a Forest of Truth and Reconciliation with more formalized spaces along the whole 1km route of the gravesite, including an exhibition hall, a memorial hall and a garden, but as the completion date of this plan is noted as December 2024 and there is no trace of any work being undertaken, it remains uncertain whether this plan has been postponed or indefinitely suspended. However, it is clear that whatever the status of this site, whether formal or informal, it will always remain as both a site of remembrance and a silent testimony to the people lost during one of many difficult periods in South Korea’s history.